Whither are we Traveling

About the document

About the document: The following document is the full version of "Whither Are We Traveling?" - a title that echoes through Masonic history, penned by one of our Craft's most prescient minds. In 1963, Dwight L. Smith, then Grand Master and later Grand Secretary of the Grand Lodge of Indiana, issued a clarion call that continues to reverberate with startling clarity today. Smith's penetrating analysis of North American Freemasonry was not just ahead of its time – it was prophetic. Now, six decades later, we find ourselves confronting the very issues Smith forewarned us about with uncanny accuracy. His concerns about leadership, declining standards, lack of education, and the dilution of Masonic purpose have not only persisted but intensified. What Smith identified as looming challenges have manifested as stark realities in our lodges. The questions he posed – about the quality of our West Gate, the depth of our fellowship, the integrity of our rituals – are no longer academic musings, but pressing crises demanding immediate attention. As we revisit "Whither Are We Traveling?", we're struck not just by its timelessness, but by its growing urgency. Smith's work stands as both a reflection of our current state and a roadmap for our necessary revival. His words, more relevant now than ever, serve as both indictment and inspiration – a call to action then, that we can no longer afford to ignore. In presenting Smith's seminal work, we're not simply studying history – we're confronting our present and shaping our future. The question "Whither Are We Traveling?" has never been more critical. As we grapple with Smith's insights, we must ask ourselves: If we've arrived at the destination he feared, how do we chart a course correction? The answers, as Smith knew, lie within the true essence of our Craft – if only we have the wisdom and courage to embrace them. – Antony R.B. Augay P∴M∴

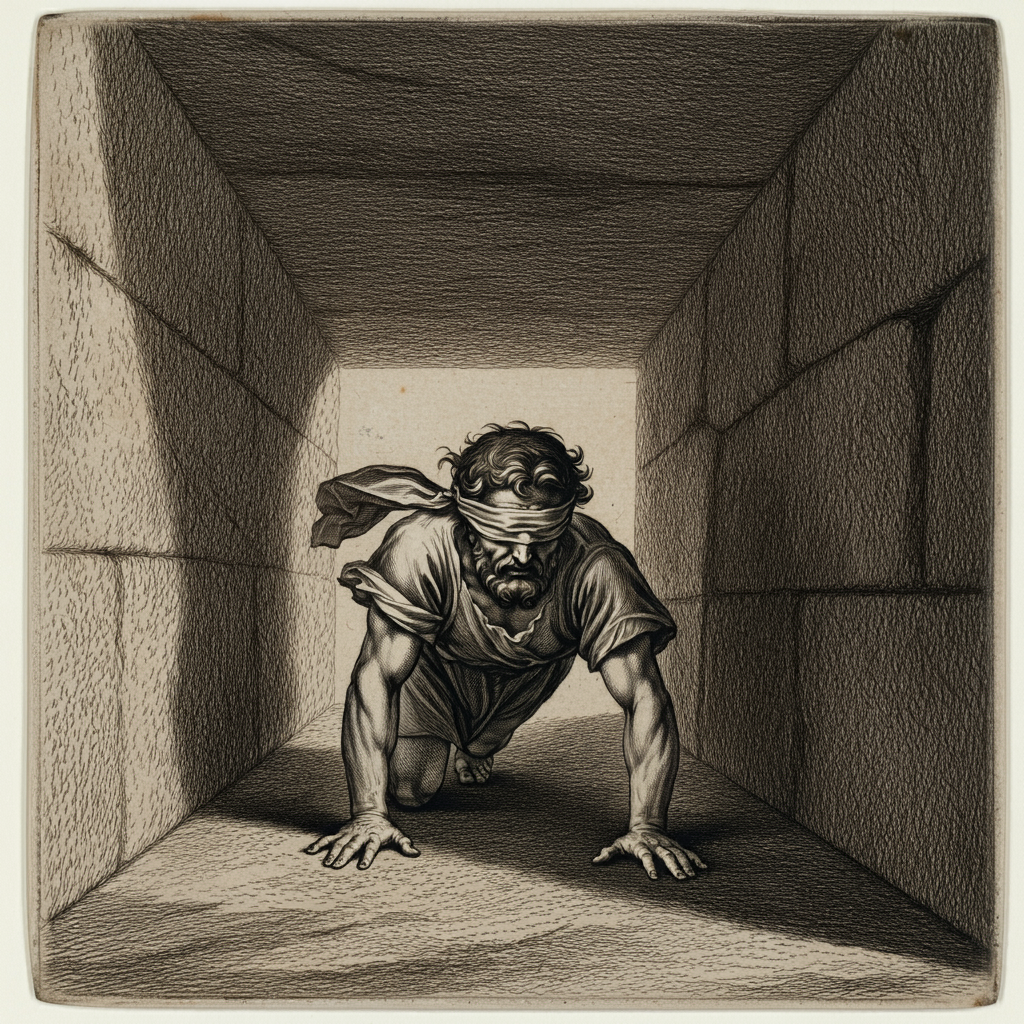

" The mere fact that men do not comprehend its purpose does not mean that Freemasonry has no purpose, nor that its purpose is outmoded – it only means that the stones are not being well hewn and squared in the quarries where they are raised." - M∴W∴ Dwight L. Smith, P∴G∴M∴

Whither Are We Traveling?

By M∴W∴ Dwight L. Smith, P∴G∴M∴

1963 A.D. – 5963 A∴L∴

Chapter 1: Whither Are We Traveling?

The Wailing Wall is crowded these days. Masonic leaders, great and small, are lined up, each awaiting his turn to lift his voice in lamentation. The figures show a falling off of membership. Attendance at Lodge meetings is not what it used to be. The thing to do is to adopt this project or that gimmick, and then all will be well. As might be expected, the projects and gimmicks are about as impossible as they are ridiculous.

For several years, the bosom-beating has been going on. Firing with a shotgun rather than a rifle, our leadership has offered little of a constructive nature. Prescriptions for the most part have consisted merely of sales talk for whatever pet scheme was being proposed. Only a few voices in the wilderness have made a mature and realistic appraisal.

I. Faulty Diagnosis

At the outset, I may as well precipitate an argument by disposing of the old favorites:

One: Whatever attendance troubles our Lodges may be having are not caused by television, nor the automobile, nor by bowling, nor togetherness, nor any of the other “busyness” in which our restless society is engaged. A multitude of activities may contribute to a decline in Lodge attendance, but they do not constitute the cause. When we complain of lack of attendance, what we really are saying is that interest is at a low ebb, for in any organization, if there is interest, there will be attendance. No amount of television or bowling or endless “busyness” can usurp the position of eminence a Lodge of Freemasons occupies in a man’s loyalty if the Lodge is in a position to command his loyalty. The ailment isn’t quite that simple. We are looking at the symptoms – not the disease. The real source of the trouble is within ourselves.

Two: Such problems as we may have will not be solved by forcing men to memorize a set of questions and answers, nor by cramming books and lectures down their throats, nor by any Big Brother Plan, nor by devoting our energies and resources to other organizations or movements, however worthy they may be. The cure isn’t that simple, either. The patient’s indisposition will not be relieved by nostrums. The treatment, too, must come from within.

II. Basic Premises

Next, may I offer what I consider to be three basic premises. Then we shall get down to cases.

First: The history of Freemasonry is one of ups and downs. If this brief period is one of the “downs,” it is nothing compared to some of the crises through which our Fraternity has passed.

Second: In our membership decline, we again see history repeating itself. It simply is a case of our sins catching up with us. We had a decade in which there was a membership influx that was both unhealthy and unhappy. We ran a production line; we counted new members by the hundreds of thousands; but we could count new Masons only by the score. Now comes the payoff.

Third: Whatever is wrong with Lodge attendance in 1962 was wrong 25 years ago when I was Master of my Lodge. I doubt seriously whether Lodge attendance ever has been “what it used to be.” I had to work by head off to sustain interest in 1937. Sometimes I succeeded; sometimes I didn’t. The situation is no different today; tomorrow and the day after it will be the same.

I repeat: we have only to look at ourselves to discover the cause for whatever unhappy days have come upon us. Our troubles are of our own making. Such corrective measures as we take must go beyond the surface; they must go to the roots of the problem or be of no avail.

Then let’s take an honest look at some of the conditions within our own house which may be contributing to a membership decline and a tapering off of interest.

III. Self-Examination

Let’s face it! Can we expect Freemasonry to retain its past glory and prestige unless the level of leadership is raised above its present position? On many an occasion in the past 14 years, Masters and Secretaries have come into my office to ask my advice on what to do about lagging interest. Again and again I have said, “There is nothing wrong with your Lodge, nor with Freemasonry, that good leadership will not cure.” I believe that.

How well are we guarding the West Gate? Again, let’s face it. We are permitting too many to pass who can pay the fee and little else. On every hand I hear the same whispered complaint, “We used to be getting petitions for the degrees from the good, substantial leaders in the community. Now we are getting. . . .” Just what it is they are getting, you know as well as I.

Has Freemasonry become too easy to obtain? Fees for the degrees are ridiculously low; annual dues are far too low. Everything is geared to speed— getting through as fast as possible and on to something else. The Lodge demands little and gets little. It expects loyalty, but does almost nothing to put a claim on a man’s loyalty. When we ourselves place a cheap value on Masonic membership, how can we expect petitioners and new members to prize it?

Are we not worshipping at the altar of bigness? Look it in the face: too few Lodges, with those Lodges we do have much too large. Instead of devoting our thoughts and energies to ways whereby a new Master Mason may find a sphere of activity within his Lodge, we let him get lost in the shuffle. Then we nag and harangue at him because he does not come to meetings to wander around with nothing to do. We are hard at work to make each Lodge so large that it becomes an impersonal aggregation of strangers – a closed corporation.

What can we expect when we have permitted Freemasonry to become subdivided into a score of organizations? Look at it. Each organization dependent upon the parent body for its existence, yet each jockeying for a position of supremacy, and each claiming to be the Pinnacle to which any Master Mason may aspire. We have spread ourselves thin, and Ancient Craft Masonry is the loser.

Downgraded, the Symbolic Lodge is used only as a springboard. A shortsighted Craft we have been to create in our Fraternity a condition wherein the tail can, and may wag the dog.

Has the American passion for bigness and efficiency dulled the spirit of Masonic charity? The “Box of Fraternal Assistance” which once occupied the central position in every Lodge room has been replaced by an annual per capita tax. That benevolence which for ages was one of the sweetest by-products of the teaching of our gentle Craft has, I fear, ceased to be a gift from the heart and has become the writing of a check. And unless the personal element is there, clarity becomes as sounding brass and tinkling cymbal.

Do we pay enough attention to the Festive Board? Should any reader have to ask what the Festive Board is, that in itself will serve to show how far we have strayed from the traditional path of Freemasonry. Certainly the Festive Board is not the wolfing of ham sandwiches, pie and coffee at the conclusion of a degree. It is the Hour of Refreshment in all its beauty and dignity; an occasion for inspiration and fellowship; a time when the noble old traditions of the Craft are preserved.

What has become of that “course of moral instruction, veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols,” that Freemasonry is supposed to be? If it is a course of instruction, then there should be teachers, and if ours is a progressive science, then the teaching of a Master Mason should not end when he is raised. I am not talking about dry, professorial lectures or sermons – heavens no! That is the kind of thing that makes Masonic education an anathema. Where are the parables and allegories? Alas, they have descended into booklets and stunts. No wonder interest is so hard to sustain.

Hasn’t the so-called Century of the Common Man contributed to making our Fraternity a little too common? We can not expect to retain the prestige the Craft has enjoyed in the past if we continue without challenge to permit the standards of the picnic ground, the bowling alley, the private club and the golf links to be brought into the Lodge hall. Whether we like it or not, a general lowering of standards has left its mark on every Lodge in Indiana, large and small.

Are there not too many well-meaning Brethren who are working overtime to make Freemasonry something other than Freemasonry? It was an unhappy day when some eager beaver conceived the idea that our Craft should adopt the methods of the service club, or the luncheon group, or the civic league, or the Playboy outfit. Whoever the eager beaver was, he lost sight of the fact that one of the reasons our Fraternity is prized so highly is that it does not operate like other organizations.

Well, that should be enough for one dose. The following pages elaborate on the ten points enumerated above. Let me give you fair warning. In the following essays I shall call a spade a spade. Some of my readers are not going to like it. But what I have to say I believe our Craft needs to hear, and it is only for the “good of the Order” that it is said.

I shall propose no bright new ideas – not one. All I am going to advocate is that Freemasonry remain Freemasonry; and if we have strayed from the traditional path, we had better be moving back to the main line while there is yet time to restore the prestige and respect, the interest and loyalty and devotion that once was ours.

Chapter 2: The Level of Leadership

Question 1: Can we expect Freemasonry to retain its past glory and prestige unless the level of leadership is raised above its present position?

A teacher in the public schools of a neighboring State cherished a long-standing desire to become a Master Mason. His petition to the Lodge in which he resided was accepted. He presented himself for the Entered Apprentice degree, but never returned. The Brethren of the Lodge concluded, I am sure, that they had made a mistake in electing that Entered Apprentice because of his apparent lack of interest. But it was not lack of interest that caused him to go out of the door, never to return. It was disappointment and disillusionment.

The performance of the Master of that Lodge was such that it constituted an insult to the candidate’s intelligence. Because the head of the Masonic Fraternity in that community was careless and sloppy and crude, because he was attempting to do something for which he was not prepared, because he was trying to give “good and wholesome instruction” on subjects he knew nothing about, a good man was lost to Freemasonry.

On first hearing, that story made a profound impression upon me. The more I have thought about it, and the more I have seen it duplicated, the more I am convinced that the Number One responsibility for any tapering off of membership, any lack of interest and attendance, rests squarely upon the shoulders of our Lodge leadership.

Yes, I know the subject is a touchy one. But in introducing it, I am only putting into print what has been whispered in the corridors these last ten years.

Take a long and thoughtful look at the names of the men who served our Lodges as Master 100 years ago – or even 50 years ago. Consider the positions of importance those men occupied in their respective communities. Then let us ask ourselves whether our present day leadership is in the same league.

One unforgettable Lodge meeting stands out in my mind. The Lodge was having trouble maintaining interest; membership was dropping; it had called for help. When the hour came for the meeting to begin, there had been no preparation. I sat around waiting for Lodge to be opened; sat around waiting for dinner to be served; sat around while the candidates were being prepared; sat around while the Junior Warden tried to enlist a craft, actually calling for volunteers, wheedling, cajoling; sat around while the Master, reluctant to close, literally begged those on the sidelines to say a few words. In short, I sat around. What was there in that meeting that would make anyone want to come again?

Nor do I exempt myself. Looking back on some of the meetings the year I was Master, it is a wonder to me the Lodge held together. Many of my meetings were such a first class bore that I would do almost anything to avoid getting trapped in such gatherings today.

If we want our Lodges to regain the position they once occupied in the interest and loyalties of men, we had better gain a proper perspective; we had better sort things out in the order of their importance. To open the discussion, permit me to make three pertinent observations:

We must pay more attention to proficiency in the East. We make a great to do over proficiency of candidates. We want to devise some method whereby new Master Masons may be forced to memorize a set of questions and answers. But we do little or nothing to insure proficiency where it really counts.

A Master is expected to be Master of his Lodge – not a weakling to be pushed around. Theoretically, he “sets the Craft to work and gives them good and wholesome instruction.” Yet what do we require for election as Master? Simply that a Brother serve as a Warden. That is all. There are no minimum requirements as to ritualistic proficiency; nothing regarding history, symbolism, philosophy, ethics, law, tradition. Only a so-called degree for Past Masters which, in far too many instances, is a farce. We elect a Master and expect him somehow to become a leader. It never occurs to us to require evidence of leadership first.

There is far more to being Master of a Lodge than the mere recitation of a ritual. We are paying the penalty of years of “mass production” practices, and a bitter penalty it is.

When Masters of Lodges are so lacking in imagination and vision that they cannot conceive of a Masonic meeting unless a degree is conferred, then we need not expect a revival of interest and attendance and we need not look for an upswing of membership short of war. I would a thousand times rather see as Master of a Lodge a man who can provide real leadership, a man who can give “good and wholesome instruction,” a man who comprehends what Freemasonry is all about, even if he cannot confer a single degree. Suppose he can not recite the ritual.

So what? There always are those who are eager and willing to do ritualistic work, but there are precious few who can provide inspired leadership.

It is high time we start looking about for the best possible leadership and enlisting the support of men who can lead. But instead, we consider only those who come to Lodge, those who stick it out in the endurance contest. We “start in line” the man who is on hand whenever the door is opened regardless of whether he has even the most elementary qualities of leadership.

If the practice of automatic ladder promotion of officers must be discarded in order to obtain the kind of leadership we should have, then by all means let us discard the foolish custom. There is nothing in the winning of an endurance contest, in itself, that qualifies a man to be Master of his Lodge.

If the so-called “line” of officers must be shortened to enable men of ability to serve their Lodges without devoting six or seven years to minor offices, then what are we waiting for? Why not shorten the line? Is not good leadership for one year more important than keeping a seat warm for six?

If Freemasonry is to command respect in the community, then the man who wears the Master’s hat must be one who can command respect. The young teacher who did not return for advancement because his entire conception of Freemasonry was colored by what he saw and heard in the East. The Master of a Lodge is the symbol of Freemasonry in his community. If he is not a man upon whom intelligent people may look with admiration, then we need not expect to reap a harvest of petitions from intelligent men.

Make no mistake. Men judge Freemasonry by what they see wearing Masonic emblems. They judge a Lodge by the caliber of its leadership. If we persist, year after year, in putting our worst foot forward, then we can expect to continue getting just what we are getting now.

Chapter 3: Asleep at the West Gate

Question 2: How well are we guarding the West Gate?

Down in Tennessee many years ago I heard one of the old stalwarts express the conviction that unless a Lodge is rejecting at least 20 per cent of its petitioners, it is either very fortunate or very careless. That striking statement has come to my mind many times in recent years.

Unquestionably the good Brother had a point. But 20 per cent, mind you, is one petitioner out of every five. (In Indiana we are rejecting about one petitioner in every twelve). It is not difficult to visualize what would happen if an Indiana Lodge were to reject one petitioner in five. The Grand Lodge office would be besieged with delegations; the Grand Master would be implored to do something to stop the “epidemic” of black-balling.

Of course, the rejection of one petitioner in five might, in the long run, be the best thing that could possibly happen to a Lodge, but we are not interested in taking the long term view. No, we want to get the new Temple paid for.

For years now I have heard the whispered complaint, “We used to be getting petitions for the degrees from the good, substantial leaders in the community. Now we are getting. . . .” Isn’t it about time we stop our whispering and say some things out loud, even if they are unpleasant to hear?

One of the conditions causing dismay in more than one Lodge is the fact that the sons of its highly respected members are not petitioning for the degrees. True, they may be busy getting ahead in the world; they may not have the money; they may not be interested. But that is not all. Why should intelligent young leaders in the community petition a Lodge if they have little or nothing in common with its members? If they cannot find in Freemasonry a social, intellectual and cultural atmosphere that is comfortable, they will find it elsewhere.

We like to repeat the story about Theodore Roosevelt, as President of the United States, attending Lodge when the gardener on his estate was Master. (We don’t say how often he went.) But I daresay if the membership of that Lodge had been predominantly gardeners, even the extrovert T.R. might have been a little lax in his attendance!

We can not escape the fact that men judge Freemasonry by what they see walking down the street wearing Masonic emblems. And if what they see does not command their respect, then we need not expect them to seek our fellowship.

Let’s face it. Thanks to two wars, inflation, the cost of building and maintaining expensive Temples, and a general lowering of standards, thousands of men have become Masons who should never have passed the ballot. The inevitable result, then, is that the Craft is not looked upon with the same degree of respect it once enjoyed.

How did it all come about?

Economic pressure, for one thing. A Lodge pays a heavy price for a new Temple so costly to maintain that membership must remain above a certain figure.

We have fallen into careless ways in the investigation of petitioners. There was the regrettable incident in my own Lodge one time when I served on an investigating committee. The petitioner was widely known; apparently he was worthy; at least nothing to the contrary had reached my ears. Accordingly I turned in a favorable report. The petitioner was elected. Several months later, from another source, the bombshell burst. Not until then did I learn that it was common knowledge about town that the petitioner was far from worthy. To correct the mistake there had to be some embarrassment and some unpleasantness. It has been a sobering thought to reflect that many of my Brethren may have questioned the petitioner’s worthiness, but gave him the benefit of the doubt simply because I had made a favorable report!

Whence came the idea that a man – almost any man – has an inherent right to become a Freemason? Is it not a privilege to be conferred upon the worthy? And whose idea was it that if a petitioner was rejected, a grave injustice has been done the petitioner? Is no one interested in seeing that an injury is not done the Lodge and all Freemasonry by electing one whose worthiness may be in question? Such an Open Door Policy is not selectivity; it is come-one-come-all. And Freemasonry is a selective organization. It must be if it is to avoid the fate of a score of fraternal groups whose names are well nigh forgotten.

Lodges are not utilizing their most capable members for duty on investigating committees. In every Lodge there are Brethren of high standards who love the Fraternity and want to see its good name protected; men who would make more than a token investigation; men would really stand guard at the West Gate. But are such men appointed as members of investigating committees? Not unless they happen to be present at a stated meeting when a petition is received. You have heard it innumerable times: “On this p’tition, I’ll ‘point Brother Joe Doak, Brother Jim Jones and Brother Bill Brown.” Just like that, the deed is done—the most important assignment ever made in a Lodge is made with no more thought than would be given to who shall turn out the lights. In the hands of Joe Doak, Jim Jones and Bill Brown rests the good name of Freemasonry, even though they may know nothing at all about making an investigation, and care less.

But Joe Doak, Jim Jones and Bill Brown were present at a stated meeting – perish the thought that one not present be used now and then! All of us have seen Masters appoint investigating committees literally hundreds of times, but on how many occasions have we seen evidence of careful thought in the selection of personnel for those committees? Men of high caliber and ability are available. Why are we not using them? Is it for fear they might turn in an unfavorable report?

You have heard me say it before and you shall hear me say it as long as I have a voice and a pen: in Freemasonry, there simply is no substitute for quality. We are accepting too many petitioners who can pay the fee and little else; too many men who have no conception of what Freemasonry is or what it seeks to do, and who care not one whit about increasing their moral stature; too many men who look upon Ancient Craft Masonry with contempt – who are interested in using it only as a springboard from which to gain a prestige symbol.

And we had better start applying the brakes while there is yet time.

Chapter 4: Pearl of Great Price?

Question 3: Has Freemasonry become too easy to obtain?

Some three months ago when this series of articles was introduced, I took advantage of a fifty-year presentation occasion to write a Masonic editorial. The recipient of the Award of Gold had petitioned a Southern Indiana Lodge in 1911 when he was making $10 a week as an apprentice printer. The fee for the degrees was $20. He thought enough of Freemasonry to empty his pay envelope twice.

A century ago it was not uncommon for men to pay what amounted to a month’s wages to become a Mason. We know without challenge that today petitioners are paying a fee which represents a week’s wages at the most – sometimes only two or three days!

When we compare the nominal dues paid to a Lodge of Freemasons with those paid to a service club, a labor union, a trade or professional organization or a country club, we begin to get a faint idea of the source of some of our troubles. And when we compare the ridiculously low fees paid to an Ancient Craft Lodge with the aggregate fees paid to other Masonic bodies and appendant groups, we begin to see clearly what is wrong.

Men are willing to pay for the privilege of Freemasonry, but we distribute the fee they should be paying to an Ancient Craft Lodge among all the relatives, the in-laws and the step-children. We place such a cheap value on the basic degrees that it is no wonder newly raised Masons end up having little or no respect for the Symbolic Lodge.

Before we are in a position to tackle some of the difficulties that beset us, we must reestablish the premise that Freemasonry is a Pearl of Great Price, worth a great deal of effort, a great deal of sacrifice, a great deal of waiting to obtain. We need to do a little preaching, perhaps, with a certain New Testament passage as the text: “For where your treasure is, there will your heart be also.”

Has Freemasonry become too easy to obtain? I am one who believes that it has. And I am not the only one. My old friend Arthur H. Strickland, of Kansas, recently wrote a thoughtful article for The Philalethes, entitles, “Who Killed Cock Robin?” Calling attention to the old axiom that what is easy to get is not much appreciated, he observes that “we have done everything that we can think of to cheapen Masonry. . . .We have cheapened the Fraternity to the point that it is seriously reacting against us.”

Has Freemasonry become too easy to obtain? To me, the question is not even debatable. For example:

Our fees for the degrees are so low as to constitute an insult to the Fraternity. When I petitioned for the degrees in 1933 the fee was $20. That was a good-sized chunk of anybody’s money in 1933, but I would have paid three times that amount. Our economic standards of today can hardly be compared to 1933, yet the minimum fee in Indiana is still only $30—and one Lodge in five charges the absolute minimum. There is not a Lodge in Indiana whose fee should not be at least twice its present amount. For a long time I have had the uneasy suspicion that the period of accent on quantity rather than quality may have started during those cut-rate years of 1933 to 1944 when the minimum fee was only $20.

Everything is geared to speed, as if a deadline had to be met. Freemasonry is no longer worth waiting for, nor working for, nor sacrificing for. Too often it is only a badge of respectability, a prestige symbol, to be obtained with the same hurry-up zeal that would be assumed in acquiring a Cadillac or a yacht. Candidate A must be rushed through the degrees before he leaves for service in the armed forces (he has heard it might be helpful to him.) Candidate B must be rushed through because he is about to move to a distant point to take a new job. Candidate C must hurry through so he can join a class in some other organization. Proficiency? Nonsense! A friendly coach can take care of that. Comprehension of the underlying philosophy of Freemasonry, its symbolism and ethics and traditions, what it is and what it seeks to do? You know the answer to that question as well as I. And we not only permit such a situation – we actually encourage it. How, in Heaven’s name, can we so cheapen Ancient Craft Freemasonry and expect anything other than contempt for the parent body?

The privilege of courtesy work has been so abused that it actually has become a detriment to all Freemasonry. What was once intended as an occasional pleasant arrangement for the benefit of a Lodge has been liberalized to the point that it now is only for the convenience of a candidate. Do you realize that a candidate for the three degrees may become a Master Mason without ever having attended a single meeting of the Lodge which has elected him? He can be initiated in one Jurisdiction, passed in another, raised in another. And yet we expect him to become a loyal and devoted Mason, with a strong sentimental attachment to a Lodge he knows nothing about, and which has done nothing except to elect him! We crave his faithful attendance, but we do about everything in our power to create a situation in which loyalty has no place. The incident in Montana in which a Brother received his fifty-year button without ever having attended a meeting of his own Lodge is not as far-fetched as we would like to think. We can learn a great deal from our Mother Grand Lodge of England and from the Jurisdictions of Scotland and Ireland, Australia and Canada, where a candidate must receive the Entered Apprentice degree in the Lodge that elected him, and in no other. It was a sad day for Masonry in Indiana when that regulation was repealed.

One of the worst offenders in the cheapening process is the well-meaning father who is too eager for his son to become a Mason. Those are hard words, but I have seen the story repeated over and over again. Sonny must be pushed through because Pop wants him to join the class in another body; because Pop wants him to receive the degrees in Germany, or France, or South America. Sonny may not have even lived within the Jurisdiction of the Lodge for years and years, but Pop wants him to join if the Lodge has to violate all the rules in the book to accomplish it. So Pop comes to the Grand Lodge office with a plea that the residence laws be set aside; that the period of investigation be waived; that Sonny be advanced without regard to proficiency. You have known him; so have I. His name is legion.

What a contrast to the spirit of that great and good Past Master of an Indianapolis Lodge who waited years upon years to hear his son express the desire to become a Mason—and who, even then, did not offer to pay the son’s initiation fee because he wanted the boy to appreciate what he was getting!

And then there are the ill-advised church parishioners who pay the fee for their minister. I have met quite a number of those ministers in my day, and have become rather cynical after working long hours trying to unravel their record of suspensions for NPD. But I must not get started on that subject.

When we downgrade Ancient Craft Masonry, submit it to all sorts of indignities, look upon it with contempt, label it as something hardly worth mentioning, permit it to have only the crumbs that fall from the table, what can we expect if Master Masons no longer give to their Lodges their full measure of loyalty and devotion?

Chapter 5: The Closed Corporation

Question 4: Are we not worshipping at the altar of bigness?

One of the most serious trend in American Freemasonry is the development of the oversized, impersonal Lodge. Even though such a condition is utterly foreign to all the traditions of Freemasonry, little or nothing is being done to correct it. On the contrary, Lodges are encouraged and expected to become even larger. What the result will be, no one knows. It may require a crisis of the first order to bring us to our senses.

The entire philosophy of Freemasonry is built around the individual – the erection of a moral edifice within the heart of a man. All its symbolism is individual symbolism; all its tradition and practice is aimed at making individuals wiser, better, and consequently happier. Mass movements simply have no place in Freemasonry, and never have had.

Then why do we worship at the altar of bigness?

For one thing, we are Americans. We measure civilization in terms of automobiles, TV sets and bathtubs. We count the number of gadgets as shown in the census reports and assume that means we are more civilized.

In the United States, the average membership of Masonic Lodges is about 252; in Canada’s nine Jurisdictions, 166; in the seven of Australasia, 117; in Puerto Rico, 92; in Scotland, 85; in England, 80; in Mexico, 70; in Germany, 53. Interestingly enough, the small Lodges overseas have little or no attendance problem. The Brethren receive a summons to attend their Lodge and they attend because it is worth attending, and because the membership is small enough that there is a congenial, closely knit unit—a community of interest, if you please. And certainly no one can accuse the overseas Lodges of not “doing things.” In their benevolent work and in their impact on community life, they put us to shame.

In the 49 Jurisdictions of the United States average membership ranges from a high of 482 in the District of Columbia to a low of 115 in North Dakota. There is even a Lodge in Kansas with some 5,700 members. (I almost hesitate to mention the fact for fear some of our itchy Hoosier Brethren will set out to exceed that record of doubtful distinction.) Only nine Jurisdictions have a higher average membership per Lodge than Indiana’s 336. They are all in densely populated States. (It will give us grave concern, I am sure, to know we are tenth instead of at the top.)

Is all this talk some curious notion the Grand Secretary has all by himself? Not at all. Some of the best minds in American Freemasonry are deeply concerned. Speaking of poor Lodge attendance, Past Grand Master Ralph J. Pollard, of Maine, observes:

“This problem is probably inherent in our American system of large Lodges and relatively low dues. It is one of the prices we pay for bigness and cheapness … Probably the best long range cure will be found in more and smaller Lodges where more Brethren can be put to work and where a warmer and more intimate fraternal spirit can develop.”

And in a masterly address before the Conference of Grand Secretaries in North America in February, 1962, Dr. Thomas S. Roy, Past Grand Master of Massachusetts, observed,

“If we permit our Lodges to increase in membership to a size inconsistent with a close fellowship, then we have created the conditions for non-attendance. The Grand Lodge of England is chartering new Lodges in England at the rate of over twenty-five a year. It is of some significance that, according to the latest figures, the average membership in all Lodges under the Grand Lodge of England is roughly eighty.”

II

What happens when we worship at the altar of bigness?

Well, in the first place, our annual waste of leadership is nothing short of a sin. Every year our Lodges welcome into Masonic membership hundreds of men with a great potential for inspired, dedicated leadership – and then we make certain they will have no opportunity to exercise it. Only one Master can serve in a given Lodge per year. We close the door on the best we have because we are too shortsighted, too solicitous of numbers and bank account to divide our membership into smaller units and utilize the manpower that is going to waste.

We provide too few opportunities for new members to use their talents, and then wonder why they lose interest and drift away. I have heard Lodge officers complain bitterly about new members coming once, twice, three times, and then no more. But why should they come when there is nothing for them to do except listen to the minutes and allow the bills? There is no place for them; worst of all, no one seems to care.

The fellowship of Freemasonry does not thrive in the mass. When will we ever learn that fellowship, that sweet and precious jewel of our Brotherhood, is an intimate thing not shared with great numbers? Some of the most priceless memories of my 28 years as a Mason center around individual contacts with just a few of my Brethren in the Lodge room and about the table – those times when we were doing things together, rejoicing in prosperity, standing steady in adversity – but always together. Thank God there weren’t a thousand of us. If there had been, I daresay my interest in Freemasonry would have withered on the vine years ago.

What must be the feeling of a newly raised member when he discovers that his Lodge, which promised him fellowship and intimate friendships, is but a huge, impersonal aggregation of strangers – a Closed Corporation! And we wonder why the membership curve goes downward, and why Masons do not attend meetings of their Lodges!

III

What are we doing about it? Just making certain that new Lodges will be formed, that’s all. Then why aren’t we at work on a long range, patient effort to correct a serious condition?

Well, first of all, remember, we are Americans, and in all areas of life we worship at the altar of bigness. Two men came to my office to talk over what had to be done to form a Lodge in a rapidly growing community. Let us call the community Suburbia. One of the Brethren made a significant statement that has been ringing in my ears from that day to this: “In my Lodge of more than 1,500 members,” he said, “I haven’t a ghost of a chance to ever go through the chairs. A new Lodge at least would give me the chance.” That Lodge was never organized, because a neighboring Lodge sent a committee to serve notice on the Brethren that “We regard Suburbia as a stock pile for our Lodge.”

Then, we are not at work organizing new Lodges because a new Lodge might cause some inconvenience to a horde of organizations now occupying quarters in our Temples. Scores of Masonic Temples in Indiana have room for one or two additional Lodges, but house only one. Instead of encouraging Lodges of Ancient Craft Masonry, which should be occupying our Temples, we shut the door on them in favor of groups which have attached themselves to Freemasonry’s coattails. Isn’t that statesmanlike thinking?

I am not worried about Lodges that are too small and too weak. That condition will eventually take care of itself. What disturbs me is the number of Lodges that are too large – and that condition is not taking care of itself.

What possible reason is there for boasting that Brotherly Love Lodge is the largest Lodge in the city or in the state? That should be cause for apology rather than rejoicing. Brotherly Love Lodge should be devoting its energies to the extension of its influence in other areas – but you can bet that Brotherly Love Lodge will do nothing of the sort. It might lose a few dozen members.

Truly, “the harvest is plenteous but the reapers are few.” Scores of Indiana cities and towns could use another Lodge, or two or three, to the good of all Freemasonry. The population is here, and, in most instances, facilities could be made available. But first we must get over our foolish idea that in order to be effective a Lodge must be large, and wealthy, and own a lush Temple in which 5 per cent of its membership or less can huddle together on meeting nights.

What happens to an institution designed to be simple becomes complex, when units meant to be small become oversize and unwieldy, when work intended for many is restricted to a handful, when something that should be intimate becomes impersonal? What happens? Look around. Exhibit A is all about us.

Chapter 6: Subdivided We Stand

Question 5: What can we expect when we have permitted Freemasonry to become subdivided into a score of organizations?

Back in my newspaper days I used to get a great deal of unwholesome amusement out of the power struggle between four church congregations in a town of less than four hundred inhabitants. All four churches were of the same denominational family and bore the same name. Each claimed to be the Real Thing. The membership of each was convinced that all others were heretics, and, as such, were condemned to eternal damnation.

What must a newly raised Master Mason who takes his Freemasonry seriously think of our subdivisions? Are they just as baffling to him as the four churches of the same name in a town of 400 were to me? Sometimes I wonder.

What must he think when he discovers that no less than 70 organizations have attached themselves to our ancient brotherhood – and that the end is not in sight? What is the reaction of the man who came into Freemasonry of his own free will and accord when he finds that a subdivision can solicit him almost as soon as he leaves the altar in the Entered Apprentice degree? And how does he feel when his beloved Lodge is referred to as the “Blue Lodge” with a rather patronizing air, and when the so-called “Blue Lodge Mason” is looked upon as something inferior, as if his neck and ears were not quite clean?

If we are interested in exploring possible causes for a decline in membership and for a slackening of interest and attendance, we had better look to our subdivisions. Of course, he who introduces the subject invites bitter criticism, but I stand firm on my conviction that in the United States we are spreading ourselves so thin that the basic unit – the Ancient Craft Lodge – is the loser. We may not end up by killing the goose that laid the golden egg, but certainly we are bleeding her white.

Yes, I am a member of many of the subdivisions. All of them have contributed much to my understanding and appreciation of Freemasonry, and I do not believe any of them can question my loyalty. “It is not that I love Caesar less, but that I love Rome more.” And I am not the only one who is concerned, — not by a great deal. Authorities by the dozen might be quoted. As long ago as 1924 the eminent English Masonic student, Sir Alfred Robins, was writing that “this sponge-like growth is spreading in American Masonry, and is threatening certain of the best interests of the Craft.”

One of the most forthright and statesmanlike pronouncements comes from Brother Noah J. Frey, 33º, Scottish Rite Deputy for Wisconsin, in an address before the Grand Lodge of Wisconsin in 1961. “Sometimes,” he said, “I wish that Masonry were not as divisive as it is, because we are all Blue Lodge members, and I fear that we lose sight of that fact and divide ourselves into smaller groups and thereby increase our inefficiency.”

And certainly Dr. Thomas S. Roy, Past Grand Master of Massachusetts, can not be accused of hostility to any Masonic body, yet in an eloquent address before the Conference of Grand Secretaries in North America in February, 1962, he was forced to declare:

“If we permit the proliferation of Masonry into rites, and the 57 varieties of bodies whose membership is dependant upon ours, let us face the fact that the attendance that goes to them belongs to us. There is a sense in which it can be said that their success is our failure. I am not passing judgment on any of them. I am a good member in some of them, and have done my share of work in them. But they all must face the fact that they must pour some of their strength back into the Symbolic Lodge. For any weakness we develop must sooner or later communicate itself to them.”

It is not basic loyalty that is at stake; it is not unity of purpose that we lack. Nor can we gloss over our shortcomings with talk about money, and benevolences, and good works. These are not the issues. We have never faced the real issues, which are:

One: The weakening of the basic unit of Freemasonry by too great an emphasis on our subdivisions, and,

Two: The unsound premise that the child is more important than the parent.

Let’s stand before the mirror and take an honest look at ourselves.

Masonic bodies and appendant organizations are actually competing for the time, the attendance, the interest, the substance, the devotion of Master Masons. I am sick and tired of all the talk about TV, and the automobile, and bowling leagues as competing influences. It is time we look in our own house to see where the competition comes from.

Like the four churches of the same name, each Masonic organization poses as the Real Thing. Each claims to have That Which Was Lost. Each is the true wrinkle if we want to appear before the world as a Big Mason – one with a collection of degrees, exclusive and affluent.

Our subdivisions have encouraged the mental attitude that when a Master Mason gains membership in another body, he then and there has outgrown the Ancient Craft Lodge. Several months after I became a Mason I was solicited by a worker in one of the recognized bodies. But I had mental reservations. “Why is it,” I asked him, “that Masons who belong to the other bodies place such a stress on those affiliations and seem to care so little about their Lodge?” Just what answer he gave me I do not remember. Really, it doesn’t matter too much, for the question never has been answered to my satisfaction. I held out for about three years before I presented my petition. Years later, when I received the degrees in another Masonic body, I overheard a past presiding officer say, “Now here, in this body, you will find the Cream of Masonry.” From that day to this, I have resented such artificial class distinction.

The newspaper obituary in my files which states that the deceased “was a member of 17 organizations, 10 of them Masonic groups,” and then proceeds to list everything that could be bought with money, is a case in point. To be a Master Mason was not enough; actually, that was of little or no importance.

And what about the Vanishing Emblem? What is wrong with the Square and Compass? Even Grand Masters have discarded it. Is it no longer a badge of honor? Must something else replace it to set the wearer apart and place him in the aristocracy?

A young man of my acquaintance was interested in petitioning for the degrees. He was interested, that is, until a Master Mason gave him the old Superiority Sales Talk, something like this: “Sure, I’m a member of Brotherly Love Lodge, but only because I have to be. The Blue Lodge, it doesn’t mean a thing to me. What I’m after is what give me the prestige and helps me in my business!”

And we wonder why attendance is poor, why interest is lax, why the membership curve goes downward!

Then there are these subdivisions that foster the attitude that, within their place of refuge, the standards of Ancient Craft Masonry do not apply. Therein lies a situation that is more than alarming; it is downright vicious. Scarcely a Jurisdiction in the United States is free of headaches brought on by some group restricting its membership to Masons, but considering itself exempt from Masonic standards. A few Jurisdictions have met the issue head on, to the good of all Freemasonry. Others have looked in the other direction, and thereby have damaged the entire Fraternity. One of these days Masonic leadership had better come to grips with the issue. The winking attitude which says, in effect, “It’s none of our business as long as you are not wearing an apron,” is unthinkingly dealing a body blow to our beloved Craft.

A serious minded young friend of mine expressed interest in Masonry until a Past Master gave him a lurid description of the antics and the carousals he enjoyed in his favorite appendant organization. That ended his interest. Mark it down. The public makes no distinction between the Master Mason who wears an apron and the Master Mason who wears some other kind of garb.

When the leadership of Ancient Craft Masonry neglects the parent body to smile upon everything which claims a relationship to Freemasonry, however remote, that leadership is not contributing to a solution of our problem; it is only aggravating it. In a single year, not so long ago, two American Grand Masters actually visited more appendant bodies than Symbolic Lodges in their respective terms of office. From one end of America to the other, Grand Masters are going up and down their jurisdictions like itinerate peddlers, promoting everything under the sun except plain, unadulterated Symbolic Freemasonry. They go to Washington to attend what used to be the Grand Masters’ Conference and find that it has become “Masonic Week” with the side-shows taking over. Truly, the tail has begun to wag the dog. And we wonder what is wrong!

Subdivided we stand, and subdivided, I fear, we shall fall.

One does not have to be more than forty to remember when the superpatriots raged over the hyphenated American, declaring it was time to drop Old World loyalties and become an American without a hyphen. Well, I am not advocating that hyphenated Masons eliminate anything that contributes to their understanding and appreciation of Freemasonry. But I am preaching a gospel of fundamentals. I am calling on our Symbolic Lodges to do a better job of upgrading themselves. And I am challenging the other Masonic organizations and appendant groups to put a stop to the down-grading of the Symbolic Lodge; to acknowledge by actions, rather than words, that the Lodge is the fountainhead of all Freemasonry; to put first things first; to look unto the rock whence they are hewn.

Chapter 7: Sounding Brass and Tinkling Cymbal?

Question 6: Has the American passion for bigness and efficiency dulled the spirit of Masonic charity?

Ask the average Hoosier Mason what has happened to Masonic charity and he will expostulate all over the place while rattling off an impressive list of organized, institutional projects of a benevolent nature. He will tell you that there is a Masonic Home at Franklin, hospitals for crippled children, research programs for mental illnesses, prevention of blindness, muscular dystrophy. If he is well informed he will tell you about a visitation program in Veterans’ Hospitals.

Pin him down and ask him what his Lodge does in the way of benevolence. If he knows where and when his Lodge meets, he may tell you that a portion of each member’s dues goes to help operate the Masonic Home; that sometimes a goodly sum is collected in voluntary contributions for the Home; . . . and besides, the dues of a hard-pressed Brother were remitted several years ago.

Press him still further and ask him what he is doing, as a Mason, to carry out his individual obligation. He will show you his collection of cards and enumerate the checks written to a dozen projects, and the income tax deductions claimed during the past year.

Then nail him to the mast and ask him, “Is that all? How long has it been since you went on foot and out of your way to aid and succor a needy Brother?” Chances are his look will be first one of astonishment; then of pity; then he will mark you down as well meaning, perhaps, but slightly off your rocker.

What has happened to Masonic charity? Time was when it was one of the sweetest byproducts of the teachings of our gentle Craft. I recall reading in the minutes of my Mother Lodge how the Brethren got together and built a modest house for the widow of a member, and on another occasion donated a cord of wood to the widow of a man who was not a Mason. Such acts were common. They were not accompanied by any fanfare of trumpets, but the community knew about them all the same, and the prestige of Freemasonry reflected that knowledge.

Only occasionally do we hear of an example of genuine Masonic charity at its best, but when we do, the impact upon the individual and community is tremendous. Why, then, do we neglect that phase of our Masonic life that can have the most gratifying results?

What has happened? Two things, I should say:

One: We are Americans, you know, and we don’t want our benevolence on an individual basis, quiet and modest, from one heart to another, even if that is the most effective manner. We want the right hand and everyone else to know what the left hand is doing. We want our charity to be well organized with campaigns, slogans, quotas and great hullabaloo. We want super-duper institutions with bronze plaques on the walls to say, like Little Jack Horner, “What a great boy am I!”

Two: When Freemasonry is operating properly, it does things the hard way. We want none of that. We want efficiency. We don’t want to be bothered by anything that will require more time and effort than the writing of a check.

Now let no man throw up a smoke screen with a charge that the Grand Secretary is attacking organized Masonic charities. I am doing no such thing. What I am attacking is the laziness, the complacency, the lack of vision with which we pour great sums of money into organized benevolences, and then, with self-righteous congratulations to ourselves, let it go at that.

I

Wherein do we fall short? Let’s look in the mirror:

Is it worth mentioning? — How often do we hear the Master call for reports of sickness at a meeting of the Lodge? In how many Masonic halls is the Box of Fraternal Assistance passed? In how many halls could such a box be found?

Do we remember? — How often are the members of a Lodge called upon to assist in person, in some act of true Masonic charity? Are they ever asked to visit the sick, or is that assignment turned over to a retired Brother who has nothing else to do? How many years can go by without a Master Mason giving of himself in an act of benevolence, or charity, or brotherhood?

Are we interested? — In far too many Lodges the payment of the annual per capita tax to the Grand Lodge is looked upon as the full discharge of all obligations pertaining to charity – an act which relieves every individual member of further concern for the year ending December 31. When I say that, unfortunately, I am not merely engaging in rhetoric; I am speaking of an actual fact.

First things last? — In far too many Lodges even the easy expedient of soliciting voluntary contributions for the Masonic Home is pushed aside as something of minor importance if there is a new Temple to build or pay for. Self-indulgence comes at the head of the list.

Crumbs from the table? — Each Lodge in Indiana is required to have a relief fund. But how much? I am ashamed to have the minimum figure seen in print. It is such a paltry sum that it could hardly do more than buy an occasional cup of coffee for a street beggar. The minimum should be twenty times its present amount.

II

But there is another side to the coin. Let’s look at that side for a moment:

Given the challenge to practice Masonic charity in its intimate and personal form, almost any Lodge and almost any individual Mason will respond with enthusiasm. More important, Freemasonry will then come to have a new meaning for them.

A few years ago the Grand Master of Missouri, distressed by the perfunctory manner in which the charity obligation is discharged, set out on a campaign to encourage Lodges to perform their own acts of charity – voluntary acts, impulsive acts, without organization, without advance planning and ballyhoo. He asked each Lodge to send him a written report of what it had done. I read many of those reports, but not without a lump in my throat.

And not only in Missouri can it happen. Right here in Indiana I have seen glorious examples of Masonic charity. For example, the story of one small Lodge which came face to face with a staggering obligation, and of how the Brethren responded to their everlasting credit. Any Lodge, large or small, which experiences the joy of giving of itself in a truly personal act of charity discovers that it literally has been born again.

Once I heard the Senior Warden of a large Lodge describe the distress in the home of the widow of a deceased Brother who was making a brave struggle to hold her family together. “It is not often we have calls for relief,” he said. “Now this is our opportunity.” Significantly, that Lodge is not losing in membership and has no attendance problems.

A Past Master of a small Lodge which levied an assessment to meet a relief emergency sat in my office and declared, “That incident was the best thing that has happened to our Lodge in the 40 years I have been a Mason, for, until then, most of us had no clear idea of the true meaning of Masonry.”

III

What does it all add up to? Well, for me, it adds up to this:

We are missing a golden opportunity for a great Masonic renaissance when we continue to let our American passion for bigness and efficiency dull the spirit of true Masonic charity. There simply is no substitute for the personal touch on the local level where it counts.

Don’t tell me how many hundreds of thousands of dollars Freemasons contribute annually to organized benevolent projects. That is not the question at stake. And don’t give me the old excuse that Lodges are prohibited from using their funds for purposes not Masonic. That, too, is avoiding the issue.

Freemasonry, if it operates as such, is a relationship with individuals, and I insist on talking about the personal efforts of Lodges and individual Master Masons. I want to know what individual Masons are doing to relieve distress – in their own communities, by their own effort.

Whenever Lodge is opened and whenever it is closed, the Senior Warden tells the Master why he was induced to become a Master Mason. One of the reasons he offers is that he might “contribute to the relief of poor distressed Master Masons, their widows and orphans.” Lip service? Sounding brass and a tinkling cymbal? Not unless we make it so.

The Brethren are here; they are as generous and kindly and thoughtful as they ever were. It is up to us to give them occasion to do what they have obligated themselves to do. Given that opportunity, Master Masons will respond in such a manner that the revival of Freemasonry will no longer be a fond hope – it will be here and now.

Chapter 8: The Decline of Fellowship

Question 7: Do we pay enough attention to the Festive Board?

Pisgah Lodge at Corydon was less than a month old then the time came for celebrating the Fest of St. John the Baptist in 1817. There was every reason for dispensing with an observance – the Lodge was small, little or no money was to be had, and no doubt it was a busy time for the Brethren, for there were forests to be cleared. But the minutes tell us that a tiny handful of Freemasons assembled and marched to the court house to hear an oration, “after which in proper order the members and visiting Brethren marched in procession to Mr. Boon’s and partook a dinner prepared according to arrangement.”

Yellowed records of any Lodge a century old and more will describe similar events at which the fine old tradition of the Masonic Feast was kept alive in spite of hardships on the Hoosier frontier. And if the faithful Secretary went on to record the amount spend for a jug of whisky with which to gladden the occasion, we chuckle indulgently and explain to ourselves rather weakly that times were different then.

Times certainly were different. And I am not at all convinced in the area of Masonic fellowship that the change has been for the better.

Back in February, when I first questioned whether we pay enough attention to the Festive Board, I went on to observe: “Should any reader have to ask what the Festive Board is, that in itself will serve to show how far we have strayed from the traditional path of Freemasonry.”

Yes, of course, every Lodge has “eats” now and then – and too often that is just the word to describe it: eats. But how often are the Brethren permitted to meet around the Festive Board for the genuine, heart-warming fellowship of the traditional Masonic feast – the same kind of close-knit community of interest that a family experiences when it gathers for the Thanksgiving dinner?

By and large, Lodges have just about abandoned that happy camaraderie which for generations was extolled by Masonic orator and poet. H.L. Haywood, preeminent Masonic author and scholar of our age, writes in his book, More About Masonry:

In the Eighteenth Century Lodge the Feast bulked so large in the life of the Lodge that in many of them the members were seated at the table when the Lodges were opened and remained at it throughout the Communication, even when degrees were conferred. The result was that Masonic fellowship was good fellowship, as in a warm and fruitful soil, acquaintanceship, friendship, and affection could flourish – there was no grim and silent sitting on a bench, staring across at a wall.

Out of this festal spirit flowered the love which Masons had for their Lodge. They brought gifts to it, and only by reading of old inventories can any present day Mason measure the extent of that love; there were gifts of chairs, tables, altars, pedestals, tapestries, silver, candlesticks, oil paintings, libraries, Bibles, mementos, curios, regalias and portraits. The Lodge was a home, warm, comfortable, luxurious, full of memories, and tokens, and affection, and even if a member died his presence was never wholly absent; to such a Lodge no member went grudgingly, nor had to be coaxed, nor was moved by that ghastly, cold thing called a sense of duty, but went as if drawn by a magnet, and counted the days until he could go.

What business has any Lodge to be nothing but a machine for grinding out the work? It was not called into existence in order to have the minutes read! Even a mystic tie will snap under the strain of cheerlessness, repetition, monotony, dullness. A Lodge needs a fire lighted in it, and the only way to have that warmth is to restore the Lodge Feast, because when it is restored good fellowship and brotherly love will follow, and where good fellowship is, members will fill up an empty room not only with themselves but also with their gifts.

Then let’s proceed to the question I keep asking so persistently. What has happened?

First of all, we must not underestimate the Puritan influence on American Freemasonry. It is that influence which, almost without our knowing it, attaches some sort of holier-than-thou stigma to the Hour of Refreshment, frowns upon anything cheerful and festive, and gives us that grim and silent staring at a wall of which Haywood speaks. How many times have you heard a pious Brother refer sneeringly to the “Knife and Fork Mason” and to the “Six-Thirty Degree,” as if there might be something reprehensible in the enjoyment of fellowship? How silly can we become?

The Brethren are not going to fill the benches until the walls bulge just to see the pious Brother clown his part in the Master Mason degree, and why should they? For some reason, Freemasonry overseas was able to escape the more dour effects of Puritanism, but on almost every facet of American life we still suffer from it. The ramifications of its influence on Freemasonry in the United States are far too numerous and controversial to discuss here, and I must not elaborate on the subject except to say that a great many of our problems today can be traced back to the period when it was deemed almost a mortal sin to eat, drink and be merry.

We must remember that this is the day of the service club. And, like it or not, our beloved Fraternity has members by the thousands who think Freemasonry should be made over to fit the Babbitt pattern; the glad-handing and first-naming, the perfunctory first stanza of “America” and the perfunctory Pledge of Allegiance, the raucous laughter, the ribald stories, the movie showing how corn plasters are manufactured. That kind of thing carried into Freemasonry becomes a travesty on Masonic fellowship, but it has crept into our Lodges, and we might as well face up to it.

The casual living of our day. By this I mean the dress of the cookout supper, the manners of the truck stop café. No Lodge can experience the true joys of the Festive Board unless the Brethren are willing to adopt some of the ways of civilization. Hard words, perhaps, but the need to be spoken.

The over-emphasis on “togetherness.” (I approach the subject with fear and trembling.) Togetherness is to be encouraged, but it can be carried too far, and has been carried too far in Freemasonry. In characteristic Midwestern style, we have gone overboard. Instead of inviting the ladies’ auxiliaries and the junior divisions to meet in our quarters and pursuing our own ways with dignity and restraint, we have literally abdicated in favor of the “family” idea. Masonic fellowship has been one of the casualties.

Then where do we go from here?

Well, first of all, we need to regain a sense of balance. For many Masons, fellowship is the most precious jewel in the Masonic diadem. It is necessary to the very existence of our Fraternity. If Brethren can not find it in their Ancient Craft Lodge, they will find it elsewhere, and the officers and workers who howl to high heaven when new members desert their Lodge in favor of appendant organizations might reflect on the fact that the Brethren simply may be in search of that which the Lodge denies them.

We need to cultivate Masonic fellowship with all our zeal – not to choke it out with trivialities, nor speak of it with supercilious scorn. We need the Hour of Refreshment in all its beauty and dignity; we need to revive those noble old traditions of our Craft. We haven’t outgrown them; we haven’t found anything better; we have lost something and haven’t discovered what is wrong!

But if the Festive Board is to serve its purpose, it must be dignified. I have said it before and I repeat: A Masonic gathering is neither the proper time nor place for dirty language or suggestive stories. And just as lacking in propriety is the sectarian preaching, and the rabble-rousing, and the political speech disguised as “Americanism.”

The Festive Board must be appropriate. It is not an occasion for comedians, nor variety shows, nor vaudeville troupes, nor tap dancers, nor magicians, nor barbershop quartets, nor homegrown movies, nor cute little child entertainers. They have their place, but their place is at the Family Night party, not at the Festive Board of Freemasonry. We can not realize the by-products of Masonic fellowship when the stage setting is so inappropriate as to be ridiculous.

And finally, the Festive Board must be Masonic. Repeatedly I am invited to Lodge banquets to deliver an address. “Give us one of those straight-from-the shoulder Masonic speeches,” they tell me in advance. “We want you to lay it right on the line.” And then, lo and behold, when I arrive to deliver that so called Masonic speech and “lay it on the line” to the Brethren, I find the room half filled with ladies and children! Bless ’em – I love them, too. But let’s acknowledge the most basic of all basic fundamentals: Freemasonry is for Freemasons.

Surely a few occasions can be set aside in the annual program of a Lodge when Master Masons can enjoy the fellowship to which they are entitled in a manner consistent with the traditions and practices of our ancient Craft.

I hope to see the day when the Table Lodge is authorized in Indiana, as it has been in the older Jurisdictions for two centuries and more. I hope to see the day when every Lodge takes pride in an appropriate observance of the Feasts of the Sts. John – something more imaginative than the tedious routine of the Master Mason degree with doughnuts and coffee afterwards!

Yes, and I hope to see the day when a Master Mason in the United States will have occasion to sing of his Lodge with the same depth of feeling that Robert Burns felt when he sang of his:

Oft have I met your social band,

And spent the cheerful festive night;

Oft, honor’d with supreme command,

Presided o’er the sons of light;

And, by that hieroglyphic bright,

Which none but Craftsmen ever saw!

Strong mem’ry on my heart shall write

Those happy scenes, when far awa’.

In Modern English1.

Often I’ve joined your friendly group,

And enjoyed cheerful, festive evenings;

Often, honored with highest authority,

I’ve led the enlightened members;

And by that bright symbol,

Which only members have seen!

Strong memories in my heart will preserve

Those happy times, when I’m far away.

Chapter 9: Bread or a Stone?

Question 8: What has become of that “course of moral instruction, veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols,” that Freemasonry is supposed to be?

A young man in his late twenties had just been elected Master of his Lodge. Determined to take the admonition to give “good and wholesome instruction” seriously, he ordered a copy of Carl H. Claudy’s The Master’s Book. It became his “volume of sacred law”; he literally slept with it under his pillow.

These three sentences in the little book impressed him so much he underlined them in red ink.

“One thing and only one thing a Masonic Lodge can give its members which they can get nowhere else in the world. That one thing is Masonry. . . . The Master whose instruction program is strictly Masonic has to send to the basement for extra chairs for most of his meetings.”

The young fellow tried it, and it worked. It was a thrilling experience for him to see Masons who hadn’t been in Lodge for years coming back regularly for Light and more Light and further Light. Nothing in 25 years has changed his conviction that the Claudy formula will fill the benches with regularity.

He is still around, by the way, though not quite so youthful. I see him every morning in the mirror when I shave.

Now, no one could have known less about adult education. All the equipment I had was a little imagination and a resolute purpose to avoid schoolroom methods. Remembering the impact of teaching by means of symbols, parables, allegories and legends, we ruled out long-winded lectures; we did not lure the Brethren with stunts or vaudeville entertainment; we did not take advantage of a captive audience because the audience was not captive – the Brethren came because they wanted to. And we had to send out for extra chairs, just as Claudy said we would.

Come to think about it, has not the Master of every Lodge an obligation to give the Craft good and wholesome instruction?

Let us proceed on the assumption that every candidate for the degrees sincerely desires the Light Freemasonry has to offer him, and expects to receive it. What happens? Well, first, we recite, recite, recite until there is nothing left to recite. Then we try to persuade the new Brother to recite also, and if memorizing and reciting do not appeal to him, we have nothing further to offer. We wash our hands of him. Disappointed, he hears that other organizations elaborate on the three degrees, and he turns to them to obtain a substitute for that which his Lodge should have provided. He asks for bread; we give him a stone.

Admittedly there is a weakness somewhere. But where? Respectfully I suggest we are weak: (1) in Form, and (2) in Substance. And just as respectfully I submit that we fall short (1) at the Grand Lodge level where the designs are placed on the trestleboard, and (2) at the Lodge level where the designs are executed.

Obviously the ramifications of the subject are too great to discuss at length. I can only plant the seed.

I. In The Sanctum Sanctorum

Let’s face it, then:

The Word. The very term Masonic Education is a liability – a frightening word suggestive of impractical theories and dull abstractions. What a blessing it would be if some creative soul could coin another: Masonic Light, or Advancement, or Instruction would be an improvement.

Our Designs. There are too many systems too hastily conceived, too much running wildly hither and yon in search of bright ideas. We pursue Masonic educational systems in the same manner that teen-agers pursue fads. Let a bright idea be advanced in one Jurisdiction and a score of Grand Masters will cry, “Lo, it is here!” Like sheep they rush to follow the bellwether. And why? If Freemasonry is universal, do we need “57 Varieties” of instruction programs? After all, Master Masons respond in much the same manner the nation over.

Our Architects. They are too amateurish. An effective program for further Light can not be designed by whoever happen to be officers of a Grand Lodge in a given year. It is a job for men with special talents. Always there should be one or two men with down-to-earth experience in adult education; a public relations man to interpret human likes and dislikes; a newspaper man to tell the story in everyday English. And all should be thoroughly grounded in the fundamentals of Freemasonry.

Our Working Tools. One of the marks of an amateur writer or speaker is that he attempts to tell everything he knows each time he writes or speaks. With rare exceptions, the printed materials for Masonic education programs are like that. They insist on telling everything. Forbidding in length and appalling in scope, they are too ponderous, too dull, too windy. Ever hear of the Tractarians? We could well emulate their example.

II. In The Quarries

Again, let’s face it:

Our Unfinished Labors. By and large, instruction is not a part of the program in the average Lodge. Such efforts as may be made are sporadic, conceived as an afterthought, treated as a stepchild. We have not caught fire with the possibilities, for we are so obsessed with question-and-answer memory work that we think all instruction begins and ends in a catechism. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Many Are Exceedingly Anxious. We know not the meaning of patience. When we do attempt to provide good and wholesome instruction, we try to do too much too rapidly. A first-grader is not handed a set of books which will tell him all he needs to know for a high school diploma. Rarely is a young Mason a Ninety-Day Wonder, yet when we instruct at all, we give him huge doses, without regard to his needs, likes or dislikes, and we expect them to do the work of a Vitamin B-12 shot. It isn’t that simple.

Rubbish In The Temple. Regrettably, too many of our programs are tied to stunts and cheap entertainment used as bait. Masonic teaching must be Masonic or it is of no avail. We defeat the purpose when we insult the intelligence of the man who seeks.

III. Winding Stairs

Then where do we start?

Most important of all, Masonic Light must come from the East. Instruction provided by a teacher who knows less than his pupil is neither good nor wholesome. “If the blind lead the blind, both shall fall in the ditch.” It has long been my contention that the place to insist upon proficiency is in the man who wears the hat and holds the gavel. If that means minimum standards, training courses, written and oral examinations, then let’s have them. I would have made a much better Master if I had had that kind of preparation.

Our approach must be an intelligent one. The program must have diversity, the doses must be small, and it must avoid dullness as a plague. Men of high intellectual attainments should have study clubs; those of limited academic training should have “capsules,” and for those in the wide range in between, the possibilities are unlimited.

Instruction must be lifted to a place of honor and respectability in Lodge affairs. Above all, it should be geared to the Hour of Refreshment – not to the lecture room nor the graduate seminar. Let self-improvement become a privilege to be enjoyed, and not a chore to be endured.

We need to discard about nine-tenths of our curriculum materials. Masonic authors whose works are authoritative and have human interest appeal could be numbered almost on the fingers of one hand. With profound apologies to local writers and compilers in every State, I maintain we could do better to stick to the classics.

Any program of further Light must be pursued continuously and with infinite patience. The parable of the Sower always should be the theme. Even though great quantities of seed will be wasted, some will take root and bear fruit – and that some is worth all the effort.

And then, humbly begging pardon of the Sacred Cows, if Plans and Programs and Systems there must be, there is only one which has stood the test of time. It is that which is carried on within the framework of the Lodge, inside its four walls, by its authority, under its control and responsible to it. Nothing should be left to whim or fancy of individuals who may be ill prepared, inaccurate or irresponsible. Textbooks, manuals, short courses, schools, forums – these should not operate as substitutes for the work of a Lodge. We can only hope that such tools may assist and inspire. But the stones must be hewn and squared in the quarries where they are raised.

Visionary? Impossible of attainment? Of course it is. The Temple within the hearts of men is never finished. No one has suggested that the building of human character is a quick and easy job. Who among us has faith to “lay his course by a star which he has never seen, to dig by the divining rod for springs he may never reach?”

Chapter 10: Bring the Line Up to the Standard

Question 9: Hasn’t the so-called Century of the Common Man contributed to making our Fraternity a little too common?

An old legend which comes to us from the Napoleonic Wars tells of a youth, too young to fight, who was permitted to carry the regimental banner. During one bitter engagement his unit was advancing on the enemy under heavy fire. In his youthful zeal the boy went so far ahead of the regiment that he was almost out of contact. The commanding officer send a runner bearing the message, “Bring the standard back to the line.” With heroic recklessness the lad sent back the ringing reply, “Bring the line up to the standard.”